The word “motion” is the first word in “motion picture industry”, and camera movement is an essential part of its visual language. I can feel how some of you roll your eyes in exasperation: “Should we really talk about pans and zooms yet again?” Well, why not? The central idea here is not how you move your camera, but why, and what effect it creates on the audience. Revisiting the basics is a perfect opportunity to unleash your storytelling and visual superpowers by looking at camera motion in a thoughtful way.

Although it’s my huge passion to deconstruct film scenes and analyze how and why they work, I won’t play the expert here. Instead, we’re going to learn from the “Vincent Laforet’s Directing Motion” course on MZed.com. Vincent Laforet is a commercial director and Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer who has a remarkable understanding of camera language. His expertise, based on professional experience and classical film theory knowledge, is a great source for learning the basic rules and how to break them. So, hop on and get ready for take-off.

When I watch the film for the second time, I use the rewind button and look at particularly powerful sequences. If I get sucked in once, I curse the director. Twice – I really curse the director. And if it happens three times, then you know they’re doing a pretty masterful job.

Vincent Laforet, a quote from his MZed course

A brief look at the history of motion

If we look at some old film examples, like “Citizen Kane“, we notice that there is significantly less camera motion than what we see today, for example. It’s not completely absent but in more cases than not, the scenes are cut together from the still-standing frames, where the only movement is the one implied by actors.

After a moment, Vincent Laforet shows another window scene that is quite similar, from Steven Spielberg’s “Close Encounters of the Third Kind”, shot thirty years later. The camera still does not move, but please note how much richer the frame has become. We see a lot of different movements here: the blinds in the wind, the trees, and the shadows falling on the house.

As the medium of film moves forward, the audience requires more and more stimulus, either within the frame itself or through the camera’s motion. People just don’t have the same attention span as they did 70 years ago, says Laforet. The course participants laugh, but we all know it’s true, don’t we?

Why move the camera at all?

Vincent Laforet's Directing Motion

Naturally, there are hundreds of ways to tell your story. Mastery of movement is one of the options to energize the frame and immerse your audience in the cinematic realms you construct. Also, it’s a wonderful tool to build tension and manipulate the audience’s gaze.

There is a simple physical explanation to it. In a static shot, your gaze continues to move across the frame taking in every bit of information you can find. Whereas when you move the camera, you can direct the audience’s focus, revealing a scene step-by-step or even confusing your viewers. Let’s watch one really long take from HBO’s mini-series “Band of Brothers” together:

The nice thing about long takes, as you might have noticed, is that they really help with overall immersion (we also have a detailed educational piece on them here). The shot above is about 2 minutes long, but you won’t find a single dead spot in it. Every moment, the camera motion and direction are motivated by a carefully coordinated choreography of action. One story after another unfolds right in front of us as we watch. It feels like we’re exploring the scenery through someone’s eyes and at the end of the take we finally meet this someone – one of the main characters.

As a director (or a filmmaker in general), one of your major tasks is to learn how to build tension and how to release it. Vincent Laforet compares this to a heartbeat line on an EKG, which, at best, should not be flat. Camera motion is only a subtle tool, but combined with great acting, composition, lighting, music, and sound design, it helps to create a powerful cinematic experience.

No camera motion and what it may mean

Before we list all the possible camera movements, let’s look at the opposite: no motion at all. It happens when the camera is locked off on a tripod, and usually, it is also a deliberate visual decision. Vincent Laforet brings as an example the following top shot from “Fargo” by the Coen brothers.

The initial idea of the film’s cinematographer Roger Deakins was to fill the entire parking lot with cars. Yet, when filmmakers arrived at the location early in the morning, they decided to leave it as they found it. How does this picture make you feel? For me, personally, very lonely – as it must feel to the movie’s protagonist, Jerry Lundegaard. He is literally at the crossroads (both in the frame and in the story at this moment). He is desperate for money, his business is falling apart, and above all, he has just ordered the kidnapping of his wife and can’t stop it. It’s a bad spot to be, no doubt. So, you wouldn’t really want camera movement here. On the contrary, the still frame supports this feeling of being frozen in time and lost concerning what to do next.

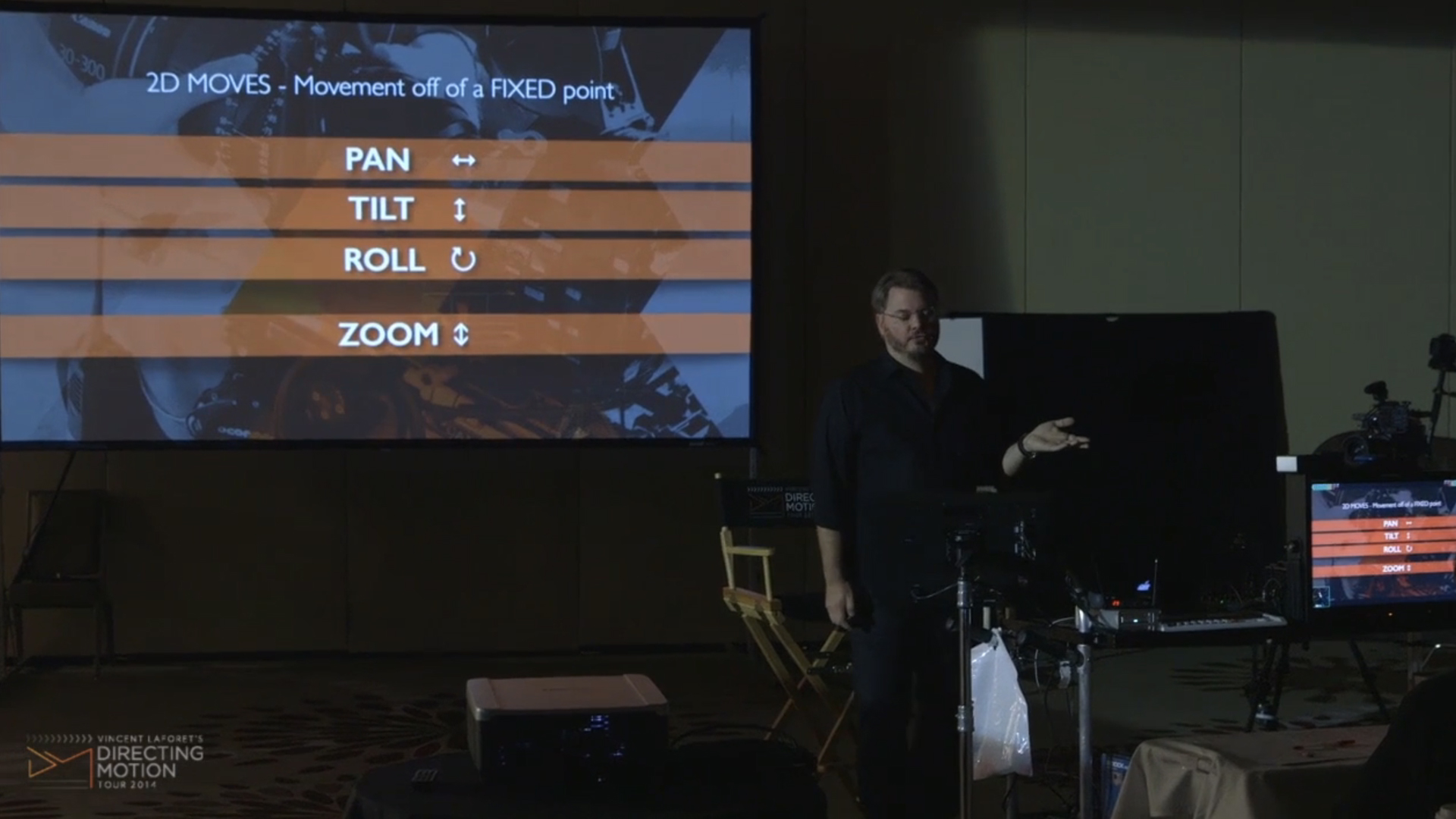

The central movement along the x-axis – pan

The first term you are definitely familiar with is pan. This is one of the most basic camera motions, which implies rotating the camera left or right along a central axis. As Vincent Laforet explains, it’s also the most comfortable way to turn our heads, which is why cinema is a horizontal medium.

What you should definitely keep in mind when creating a pan shot is the direction. Rotating the camera from left to right feels easier and more natural to your audience than right to left. Why? This is the direction in which we naturally read. Moreover, as I’ve learned, it can be subconsciously linked to the concept of time. Left to right signifies moving forward, while right to left implies a journey back into the past.

Of course, it doesn’t mean you have to always stick to the rules. Yet, if you’re aware of this subtle effect, you can play with it and use it as a device throughout the entire film. (For example, always panning to the right when things are good, and to the left when something bad is happening). This can be a tool in your visual subtext kit (head over here to read more about it). One of the great pan examples is the ending scene of “American Beauty” by Sam Mendes.

Have you noticed how and when the camera starts panning away from the protagonist? There might be two reasons for that. The first is the practical: the creators don’t want to show his head being blown off. The second one is building tension. The moment the pan begins, the viewers anticipate what will happen. If the focus had stayed on the character’s head, it would have left the possibility of a different ending. But the camera moves away, and we know for sure that the character’s fate is sealed.

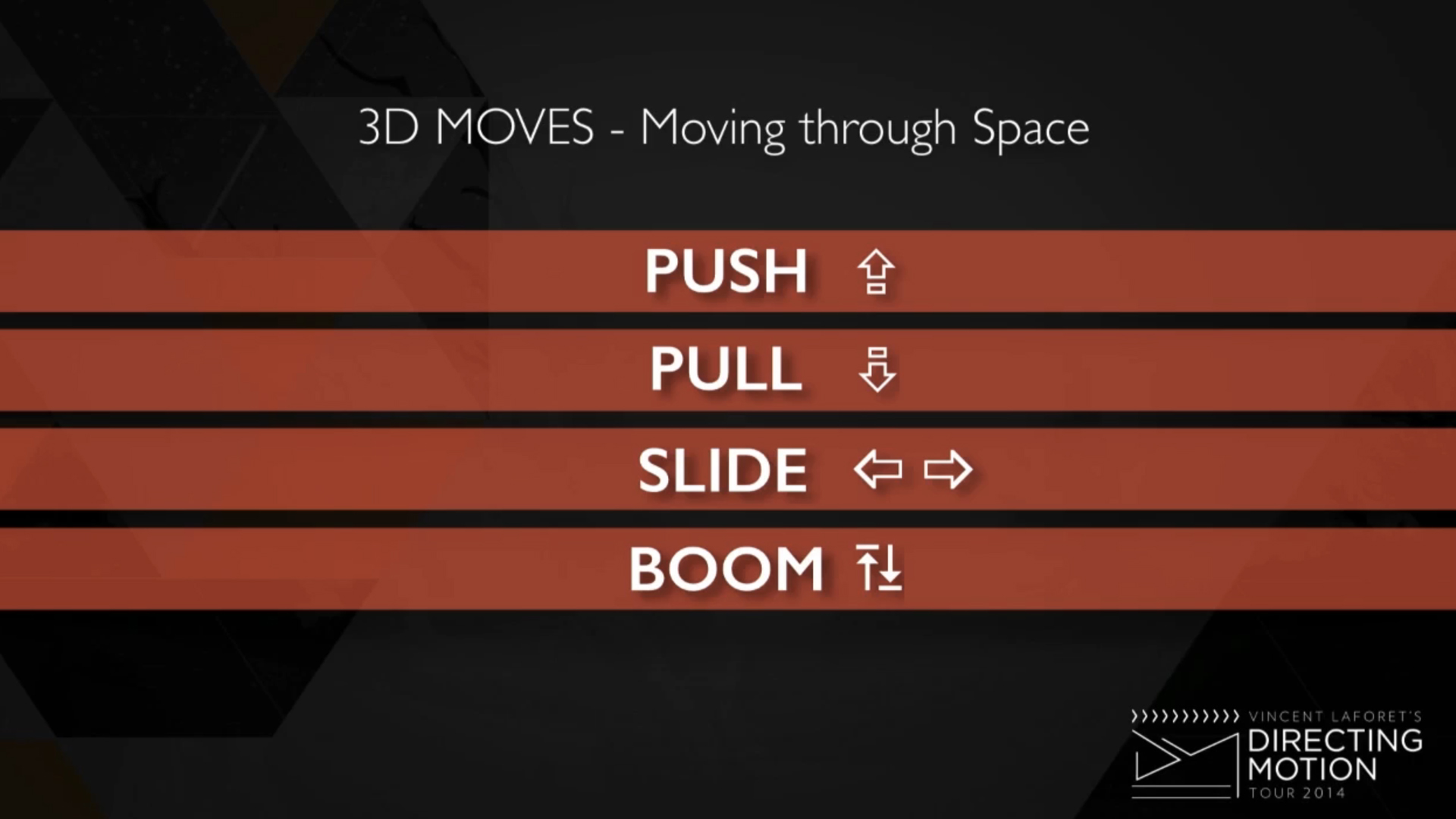

Slide and how it differs from pan

In cinematography language, slide means to move the camera left or right laterally within a 3-dimensional space. Vincent Laforet explains that it’s like taking a side-step. Some people may call this motion “dolly”, and it’s totally okay, yet strictly seen, the official name is “slide”.

Compared to panning, which feels much more two-dimensional, sliding the camera enables us to play with the depth in the picture (especially if we include foreground elements in the composition). Also, it helps follow a character, staying directly beside them. For example, take a look at the beginning of this scene in “The Shining” by Stanley Kubrick.

The sliding camera in this shot not only transfers us from one room to another but also almost seamlessly switches between Jack’s condition: from reality to his psychosis.

Tilt and boom camera motions

On the y-axis, we have tilt and boom. Tilt means to rotate the camera up and down along a central axis. As Vincent Laforet points out, all basic camera motions are based on human movement. So, when you decide which one to choose, think of how the real-life move would make you feel. Is someone creeping closer? Possibly, you feel uncomfortable. Looking down on you? Small and insecure.

In this top-down shot in the scene from Terry Gilliam’s “Brazil”, the camera slowly tilts up. The character has just been given a new job, and a more influential position awaits just beyond those doors. This move seems very logical, even if it’s not the most conventional camera framing per se.

To boom means moving the camera up or down through space, or as Laforet describes it: “rise up, fall down”. Under which circumstances would you use this camera motion? From a storytelling perspective, for example, when someone becomes successful, or on the contrary, when a spirit leaves a dead body and rises to the sky. One of the common uses of a camera boom is to show the passing of time.

Zoom versus push-in and what feeling they create

My guess is you are completely familiar with the difference between zooming and moving the camera through space (pushing or pulling). However, it only makes a difference if you underline the depth change in the shot. When your character or object is set against a flat background, you can simplify the motion and use a zoom instead, like in the example from “Psycho” below. The effect will be the same.

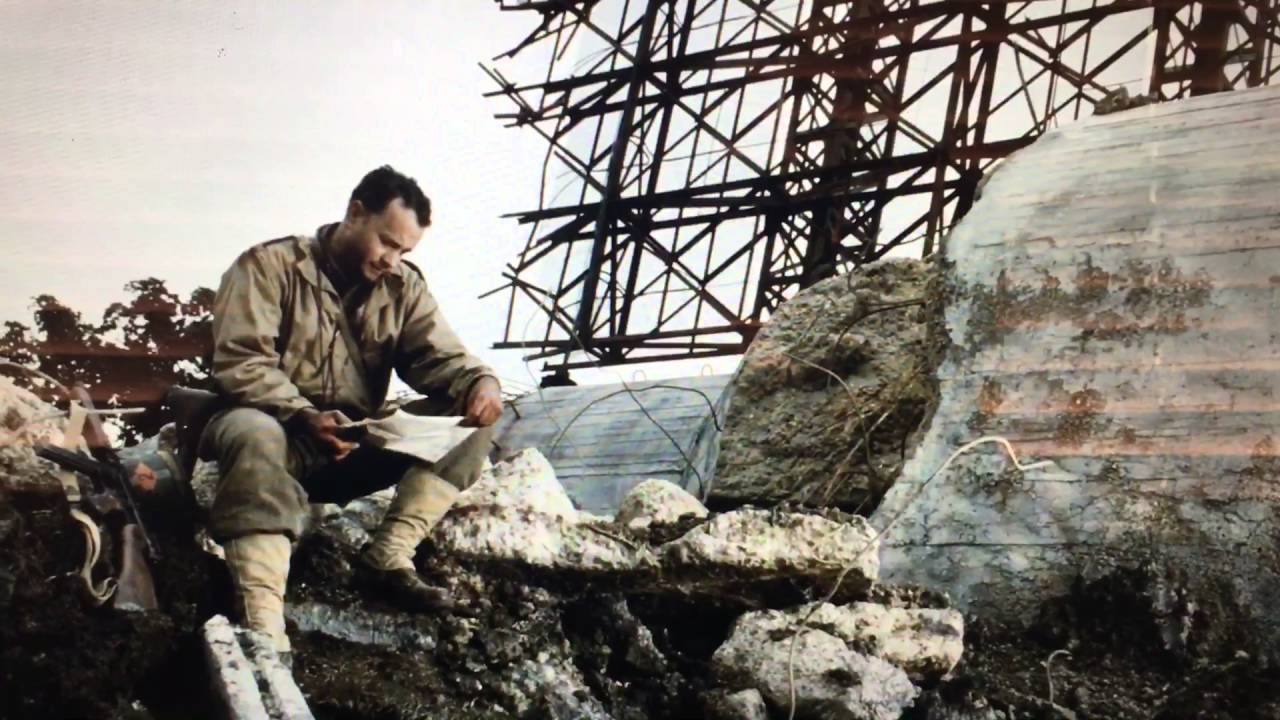

So, what can a push-in tell? Vincent Laforet analyzes its effect on the example from “Saving Private Ryan”. After the loss of one of his soldiers, Captain Miller gives way to his emotions as the camera slowly moves closer and closer without interrupting cuts. In real life, we would probably look away at some point, but here, we don’t have a choice. We’re bound to watch him, relate, and build an emphatic reaction towards his emotions. The cut comes only when the character decides to pull himself together, and it signifies a sudden shift.

Pulling out is the opposite motion of pushing in. The camera “backs up” through the space. This move may help us to get to another place, or hint at a danger coming up our way. It’s also a very strong tool to reveal visual information to the audience on our own terms, creating – again – tension. A good example would be this shot from “Atonement” by Joe Wright (I’m talking about the first 15 seconds):

Roll as a rare camera motion

A very rare art of camera motion is the roll. Unlike how we naturally perceive things in real life, the camera rotates either clockwise or counterclockwise around its central axis. This motion can induce a profound sense of disorientation. But if this is what you’re looking for, why not?

Summarizing and making more complex movements

All the movements mentioned above can be divided into 2D and 3D moves. This is how Vincent Laforet structures them:

Images source: MZed

Other, more complicated camera motion will always incorporate these fundamental techniques. We can combine each and every one of them to support the rhythm and the development of the story. A powerful example, which Vincent Laforet concludes his lesson with, is the following scene from Steven Spielberg’s “Empire of the Sun”. No wonder people call Spielberg “the master of motion”.

Now, since we’ve revisited the basics of camera motion, we can go even deeper into the why and why not of how and when to move the camera; how to enhance the story with precise blocking; what sequencing means; and instructing any crew on how to execute your creative vision effectively. You can learn all this and much more in the 6.5-hour “Vincent Laforet’s Directing Motion” course on MZed.com.

What do you get MZed Pro?

As an MZed Pro member, you also get access to nearly 300 hours of filmmaking education, plus we’re constantly adding more courses (several in production right now).

For just $30/month (billed annually at $349), here’s what you’ll get:

- 54+ courses, over 850+ high-quality lessons, spanning over 500 hours of learning.

- Highly produced courses from educators who have decades of experience and awards, including a Pulitzer Prize and an Academy Award.

- Unlimited access to stream all content during the 12 months.

- Offline download and viewing with the MZed iOS app.

- Discounts to ARRI Academy online courses, exclusively on MZed.

- Most of our courses provide an industry-recognized certificate upon completion.

- Purchasing the courses outright would cost over $9,000.

- Course topics include cinematography, directing, lighting, cameras and lenses, producing, indie filmmaking, writing, editing, color grading, audio, time-lapse, pitch decks, and more.

- 7-day money-back guarantee if you decide it’s not for you.

Join MZed Pro now and start watching today!

Full disclosure: MZed is owned by CineD

What is your favorite camera motion? In which situations would you use it? Do you have a perfect film example for this topic that we didn’t mention above? Share it with us in the comment section below.

Feature image source: a film still from „Empire of the Sun” by Steven Spielberg, 1987.