Here’s a tip for recording dialog that those of a more visual stripe may find both surprising and useful.

Roles are blurring. As media distribution has accelerated and the cost of production equipment has come down, many check-writers have expected labor costs to follow suit, and technicians of various stripes have had to become competent at non-traditional tasks.

In the realm of audio for video, this has brought some over-simplification of what is in fact a craft every bit as complex and challenging as cinematography. I’ll leave the in-depth instruction to the seasoned recordists, but here’s a tip from the sound world that may just kick your one-man-band dialog recording up a notch or two.

In the film and video industries, the iconic status of the shotgun mic, wrapped in bedraggled feline, has led many shooters to think of it as an accepted all-around microphone. For many, learning of the directional pickup pattern of this instrument is quite enough to convince them that it is the right tool to live at the end of their boom ninety percent of the time.

As it turns out, the shotgun mic is one of the most specialized microphones of recording history, and its design makes it optimal for only a slim range of applications.

Interference Tube Design

How does a shotgun work? The basic principle is that of the interference tube. Omni-directional microphones have a diaphragm that is open to the world on one side, but almost fully sealed on the other side.

Interference tube mics on the other hand are much different. They allow sound waves to arrive at the diaphragm from the back as well, but they require that these waves first travel through a long tube with slots cut into it. This tube and these slots are tuned in such a way that there is a time difference between a given impulse (e.g. the sound of a ‘p’ from a mouth 90 degrees off axis from the mic) reaching the front of the diaphragm and that same impulse reaching the back.

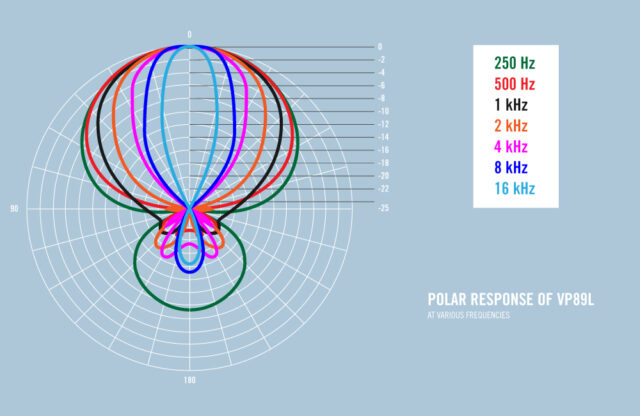

Polar Response of the Shure VP89L Shotgun Mic. Notice that off axis, the mic is more sensitive to lower frequencies and less to higher frequencies, resulting in a very colored sound.

This time difference results in an interference pattern: because sound waves are essentially waves of alternately increasing and decreasing local air pressure, a time difference of this kind, if it is tuned just so, can result in the waves canceling each other out (or interfering) when they meet. However, this tuning can only be optimized for a given target frequency range, as the interference tube length is different for different frequencies.

This design is highly specialized. It is excellent for a slim range of applications. However, its only real virtue is its directional — or focused — pickup pattern. To attain this end, it makes two very important compromises. These are inherent in the design logic, so no matter how high end the product is, these compromises will never fully be eliminated.

Sound Quality

Once again, the “directionality” of shotguns — their ability to record sources directly in front of them at a higher volume than sources from other directions, is actually only fully achieved within a target frequency range. Manufacturers tune the tube like an instrument, adjusting its length and other parameters to make its directionality apply most to the frequencies it will likely be used to record, generally the human voice.

But there’s a problem. A given human voice generally peaks in a predictable frequency range, but its entire scope is more extensive. Furthermore, environmental variables, such as the acoustic properties of a room, may emphasize certain tones more than others, which can cause serious problems.

If you are using a mic that is more directional at one frequency range, but relatively much more sensitive to bassier sounds from any angle, what happens to the lower vocal frequencies when they bounce off of a wall and arrive at the shotgun from the side, entering its row of slots? Of course what happens is not pretty, and it is very hard to disentangle in post.

Wind Sensitivity

Thus recordists familiar with this effect have recommended using shotguns only outside, where there are no flat surfaces to reflect low frequencies into the microphone. As fate would have it, the very design that makes shotguns function — their tuned rear entrance to the diaphragm, results in an extreme sensitivity to wind. A simple thought experiment will illustrate why.

Imagine you are holding a piece of kitchen plastic wrap, slack between two fingers. If you blow across the surface of this, it will vibrate very quickly and easily and produce a loud, flatulent sound. Now imagine you formed this same piece of thin plastic into a balloon and inflated it. If you blow across the surface of this balloon, it will now have very little effect.

The thin, light-weight diaphragms of microphones behave in a similar way. The less pressure difference there is between the two sides of the diaphragm, the more susceptible to wind-noise it is. As explained above, shotguns employ “interference tubes,” and this design involves an atmospherically open back to their diaphragm.

This open-backed design results in a much less pressurized diaphragm, and thus a much higher wind sensitivity. To solve this, recordists have, as we all know, resorted to large and expensive blimps and “dead cats.” Once again, in certain scenarios, this combination of technologies is an invaluable tool set that more than justifies it significant cost and quality sacrifices. It is hard to imagine many films being made without this powerful technology being available for cases when nothing else will do.

However, it would be foolish to think of the shotgun mic as a first-resort, all-around solution, either indoors or outdoors, but especially for shooters who regularly record indoor dialog in a relatively quiet space. In these situations, nothing could be less appropriate.

So What’s a Good All-around Dialog Mic?

Of course the answer to this questions depends on a number of things. For instance, if you can only afford one boom microphone and you regularly shoot in very noisy environments, then a decent quality shotgun may well be the right all-around tool.

If, however, you shoot a lot of interviews indoors, and the room is relatively quiet, then even those who can only afford one quality mic will likely be better served by a supercardioid. These microphones are nearly as directional as commonly used shotguns, but their sound quality is generally far superior.

Two of the most loved of these microphones among dialog recordists are the Schoeps CMC641 and the Sennheiser MKH 50. For those on a budget, other respected manufacturers make very capable instruments at a more affordable price point. In particular, the Audio Technica AT4053b is absolutely worth a listen.

While an in depth look at supercardioid options is a subject for another post (watch this space!), here’s a brief overview of these three microphones to get the ball rolling.

We will start with my personal favorite, the Sennheiser MKH 50. While it is not a perfect instrument, this microphone has a lovely build quality, an equally lovely tone, and like most supercardioids, is very versatile. It is not a perfectly accurate mic, but rather has a bit of color, a subtle emphasis in the low-mid region of the vocal range. This slight coloration is flattering to most voices, and is similar to the post processing often favored for vocals.

For those on a tighter budget, Audio Technica has established itself as a reliable source of very good quality microphones for the money. While technically a hypercardioid, the AT4053b is also worth considering. It is not perfect, but produces a respectable off-axis neutrality and a pleasing sound for most voices. Especially given the noisiness and other problems associated with lower quality shotgun mics, Audio Technica’s solid hypercardioid fills a very important gap in the market.

The Schoeps CMC641 is the most accurate and precise option, and it’s a thing of beauty. While it is not quite as rugged as the Sennheiser, whose products are known to be particularly water and shock resistant, Schoeps is a very high quality manufacturer whose products are reliable. If you prefer to record dialog and other sources in a rigorously accurate way and plan to leverage the freedom to tweak the precise tonality of each voice in post, it is hard to do better than the Schoeps.

Conclusion

It may be time to revise the common advice that a lapel and shotgun are the right first investments for film and video shooters. While shotguns are invaluable tools, the simpler technology and superior sound of supercardioids (and sometimes hypercardioids) make them a very nice middle-of-the-road solution for many uses.

What do you think? Is it time to moderate the shotgun-philia of the video industry? What experience have you had with different boom microphone types? Let us know in the comments!