How close is too close? Well, it depends. In real life, there are limits to how closely we can approach and perceive an object (unless we use a microscope or similar equipment). In film, however, there are no such boundaries. We can observe on a large screen how the pupils of the character’s eyes shrink in horror or how a mosquito inserts its long proboscis into human skin. As you surely know, there is a term for this particular shot size: extreme close-ups (or ECU). In this article, we’re going to discuss how and when to use them and also witness how their profound power unravels in famous film examples.

Fifteen years ago, when I was studying to become a TV journalist, one of our professors told us that close-ups and ECUs are perfect inserts for an interview or a reportage. He suggested using them only as B-roll elements when you need something to cut to. All these years later (alongside a dedicated film education and gathered practical experience), I know for sure: this is not true. Extreme close-ups exert an extreme impact on viewers (pun intended). Therefore, if we choose to use them, we must do so with care and a clear understanding of their role and function in visual storytelling. Let’s dig in!

An extreme close-up and its variations

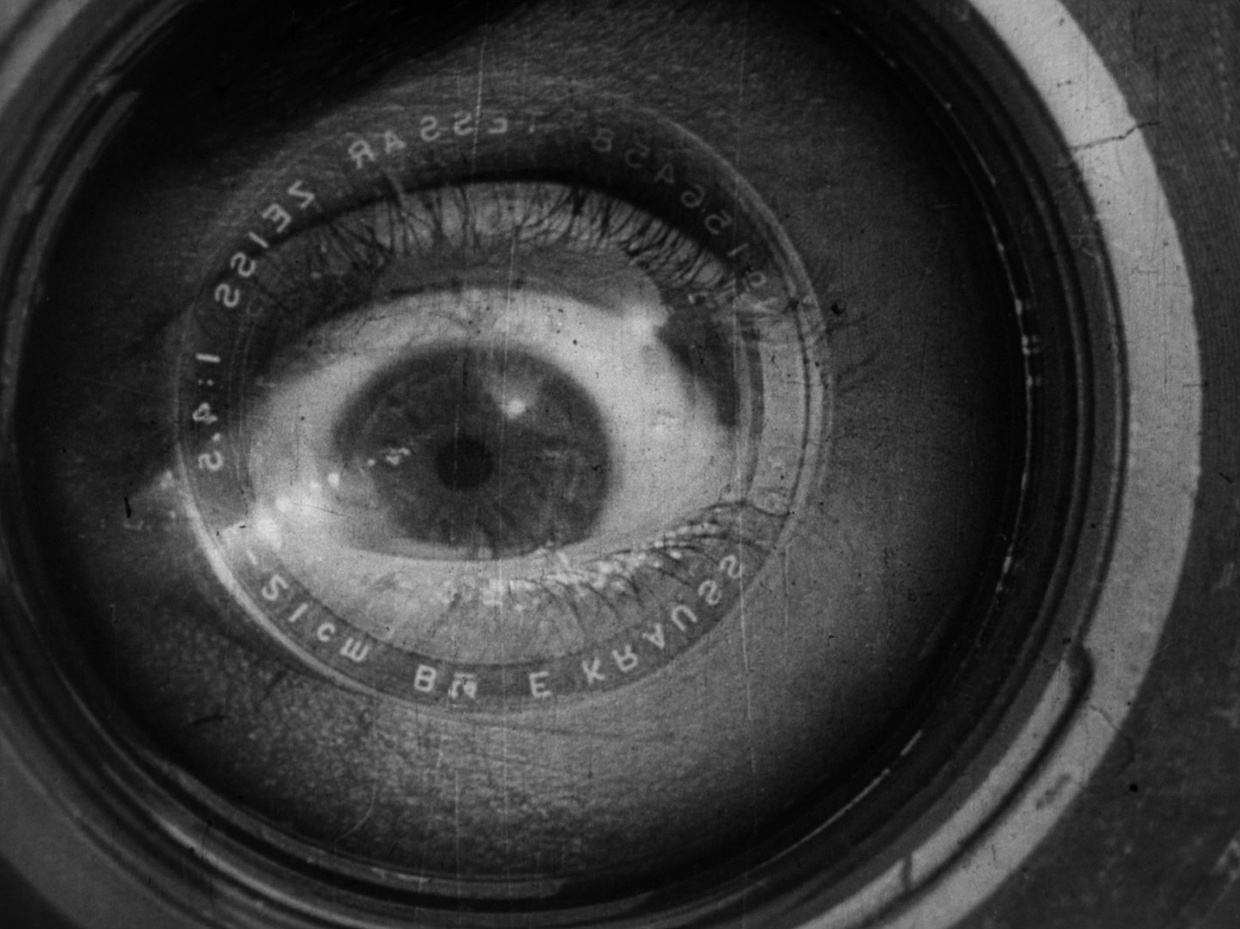

As the name suggests, an extreme close-up frames something extremely close, whether it’s a detail of a face, a specific object, or an element of something bigger. In our MZed-course “Fundamentals of Directing,” filmmaker and educator Kyle Wilamowski offers a subsequent definition:

In traditional film terminology, an extreme close-up is the tightest shot where the contents within the frame are still recognizable. The difference between a normal close-up and an extreme one lies in the focus on details. For example, while the former shows the character’s face, the latter pushes even further, framing only the eyes or the lips and making them larger-than-life.

Of course, we can achieve this kind of composition in a variety of ways. You can take any lens – wide, normal, telephoto – and use it for an extreme close-up. Each of them will provide the shot with different optical characteristics and, yes, a different feeling. Take a look at the two subsequent film stills and compare them:

The example from “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” is an ECU made on a wide lens, visibly warping the face of Johnny Depp’s character to support the overall notion of an altered state of consciousness. (As you probably remember, they had “two bags of grass, seventy-five pellets of mescaline, five sheets of high-powered blotter acid,…”) Whereas the extreme close-up from Fincher’s “Se7en” uses a long lens to focus solely on William Sommerset’s eyes and the reflection of the important clue in his glasses. It drives our attention only towards this detail, blending out the rest.

Narrative use of extreme close-ups

And that’s the thing with extreme close-ups. Like other elements of visual storytelling language, they can create various feelings and follow different goals, but they are never “just B-roll inserts.” Or at least, they shouldn’t be.

To unleash their full power, consider two important things before using them. First, when and how often do you place an extreme close-up in your cinematic story? It can be a rare punch, catching us off guard. In that case, your ECU will punctuate a particular moment, dramatically amplifying its impact. The opposite would be placing several extreme close-ups one after the other or even making a whole scene out of them, evoking a disorienting and oftentimes uncomfortable feeling in the viewers. Or you can build up to your ECU, gradually raising the tension. Classic Westerns were fond of this technique. Here is a prominent example from “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly” – the final duel, where the scene starts with a super wide shot and gradually moves closer until only the eyes are visible, right before the first gunshot (starting at 04:51):

The second important question is why. Why do you need an extreme close-up at this particular point in the scene? What is its narrative purpose? How do the eyes of the characters advance the story?

Think of it as the famous Chekhov’s gun (especially if you’re framing an object tight in your shot). If it hangs on the wall in the first act, it should fire in the next one. Otherwise, don’t put it there.

Conveying emotions in extreme close-ups

As I already mentioned, extreme close-ups can serve a variety of narrative purposes. Let’s examine some important ones.

Of course, coming that close to the face of an actor is a powerful way to craft a bond between the character and the viewer; it lets us crawl inside their heads. (Christopher Nolan uses this dramatic effect a lot in “Oppenheimer”, and we wrote about it here). As we see every detail, even a tiny twitch of the lips will convey and transfer an emotion – let alone, when these lips scream:

This film still is from Psycho’s famous shower scene. It’s a scream, and we only see the actress’s mouth. Could this action be framed as a wide shot? Sure. But in this particular moment, as Kyle Wilamowski explains in the MZed course “Fundamentals of Directing,” by being so close to this detail, we feel the scene so much more intensely and in the extreme. The choice of ECU makes it more personal and heightens everything that’s going on.

Often, filmmakers rely on extreme close-ups to highlight a character’s reaction to a pivotal moment, an internal struggle, a sudden realization, or just a significant experience. For example, in “First Man,” Damien Chazelle cuts to an ECU of Ryan Gosling’s eyes shortly before his almost-crash at the beginning of the film, when he successfully launches on Gemini 8, and, of course, right before his legendary lunar landing.

Not missing any details

Another function extreme close-ups bring to the table is that they can provide the viewers with context they wouldn’t otherwise have been able to capture. This is really helpful when you need to communicate something story-relevant but don’t want to rely on dialogue or, worse, exposition.

That’s why we often see a clue, a letter, or an important text message on the phone in films. Yet even a punctuated detail of something bigger or an object shown up close can say more than a thousand words. For instance, do you remember this spinning top from “Inception”?

We need to see it in an ECU once so we remember its significance as Cobb’s totem, which helps him to detect whether he is sleeping or not. It helps us to recognize the object in the final scene, spinning. The film ends on it, and Nolan leaves us wondering: Will the top fall? Is the protagonist awake, or are we still in the dream world?

Telling a story through extreme close-ups

You can go even further and use extreme close-ups to underscore pivotal dramatic moments. That’s what Quentin Tarantino does brilliantly in “Kill Bill: Vol. 1”(he is, in general, an ECU fan, as we know).

Uma Thurman’s character lies in a coma after being shot. A mosquito lands on her skin and starts sucking her blood. We see the bite impossibly close. So close that the insect’s proboscis fills up almost the entire frame. When you watch the film for the first time, you may wonder: Why? That’s bizarre! However, Tarantino does it for a good reason:

Yes, this bite is a catalyst and a life-changing event. It awakes The Bride from her coma and launches her journey. Tarantino chooses to shoot the following flashback as a row of extreme close-ups as well, possibly to emphasize its meaning for her story. Or maybe, simply because he loves extreme close-ups, and here are some other ECUs of his, just to enjoy:

The stylistic choice for particular sequences

Finally, you may go for extreme close-ups as part of your visual language to separate particular stories or filmic worlds from each other. After all, ECUs not only emphasize details. They do it by hiding everything else, and that could also be an interesting tool from the narrative perspective.

For example, in “Dune,” Denis Villeneuve uses a lot of extreme close-ups in the spice vision sequences experienced by young Paul Atreides from time to time. This choice of shot size creates a dreamy feeling: the notion we see something but can’t quite catch all the details, that some parts are missing and the overall picture is incomplete.

Conclusion

Extreme close-ups can be dreamy, punchy, tense, significant, emotional, and, yes, extreme. In fact, they are anything but “just inserts.” Yet having this power in your filmmaker’s hands comes with responsibility: You ought to analyze what effect they create on the audience in a given moment and decide why you use them. What for? What do they tell us? As with other filmmakers’ tools, that’s where the craft of cinema lies.

What about you? Do you often use extreme close-ups in your movies? If so, what function do they usually carry? Can you think of other prominent examples and dramatic purposes for ECUs? Let’s talk about them in the comments below!

Feature image: film stills from “Dune: Part One” by Denis Villeneuve, 2021, and “Blade Runner 2049” also by him, 2017.

Full disclosure: MZed is owned by CineD.

Additional source: “Cinematic Storytelling” by Jennifer Van Sijll, 2005.