Time is relative. In films, even more so. As filmmakers, we have developed a huge bundle of tricks for speeding it up, slowing it down, freezing it, or disrupting it. We can even glimpse into the past or future if we need to. Film time is a huge topic on its own. Here, though, we’ll narrow it down and take a renewed look at one of the most basic settings every DP or videographer encounters daily: frame rate. Where do conventions like 24fps come from, when can we ignore them, and how to use frame rate as a storytelling tool? Let’s explore it together by breaking down some exciting film examples.

The reason why we – filmmakers – alter time in movies is simple. Our goal is not to depict reality 1:1 but to create a dramatic story. That’s why we include only those moments that contribute to the narrative, leaving out the rest. However, even without the editing, we sometimes manipulate time directly within the shot. Why? Hopefully, your answer is not just “because it looks cool” but “because it enhances the story”.

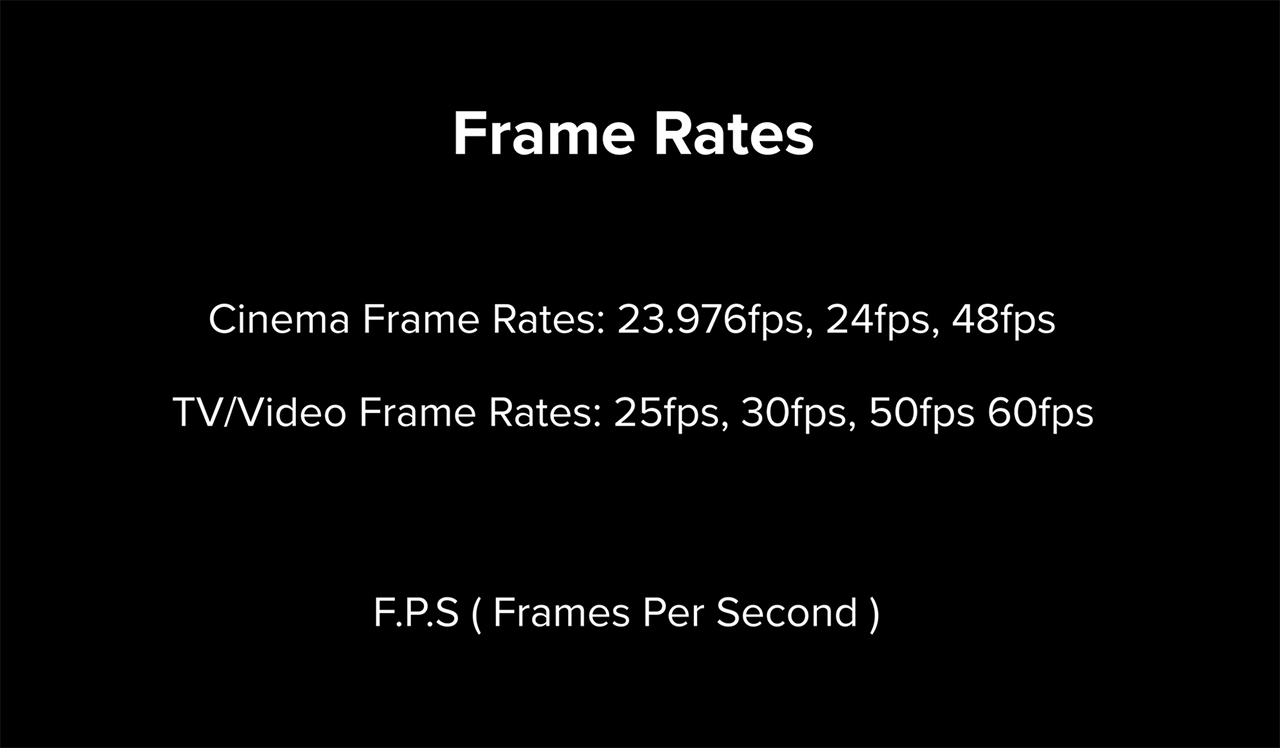

Conventional frame rate camera settings

When you start taking the first steps in cinematography, you quickly learn the basic camera settings. Frame rate is one of them, alongside ISO, aperture, and shutter speed. As world-renowned DP and educator Philip Bloom mentions in his MZed course “Filmmaking for Photographers”, creating a “filmic” look requires certain rules and limitations. They include, for instance, that cinematic videos are filmed and projected mostly in 24fps or 25fps (short for “frames per second”). The former is for movies, and the latter is for TV productions outside of the US, or so the convention goes.

The other rule is that your shutter speed should be double your frame rate. For instance, if you film at 25fps, your shutter speed should be set to 1/50th. As Philip Bloom explains, this allows us to capture the most natural movements, achieving motion blur, which is convenient for our eye. The country where you shoot also plays a role in this decision. Globally, we have two electrical outputs: 50 hertz (often referred to as the PAL system) and 60 hertz (NTSC system). Let’s say you’re in England, a 50-hertz country. Setting up your camera to 25fps and 1/50th shutter will perfectly match the frequency of the electricity supply. However, as soon as we break the rule or go out of step, we may experience flickering from domestic lighting:

Images source: MZed

If you want to play with frame rate settings (for various reasons), then you should use professional film fixtures or shoot outdoors with natural daylight. Both solutions won’t cause you problems with flickering. In the US, the electricity is 60 hertz. But often, instead of shooting at 30fps with a 1/60th shutter, they prefer to go for 24fps with a 1/48th shutter and avoid domestic lights in the shot. Why? Because 24p is still the sweet spot for a cinematic look.

Filmmaking for Photographers

Where do 24 frames per second come from?

We learn it by heart in film schools, like a mantra: Use 24fps (or 23.976 fps). Some people are even convinced this frame rate looks more natural and “true to life”. No, the reason for this exact number has historical roots. By trial and error, early filmmakers found out that the illusion of motion starts at 16fps. Falling below this threshold, the brain perceives separate still images instead of connecting them to a consistent film. All the silent movies were shot using this discovery (at around 16-18fps) but then projected closer to 20-24fps. That’s why when we watch Charlie Chaplin’s works, they look slightly sped up, which enhances the comedic effect:

The higher the frame rate, the better the illusion – creators understood it even back then. (In fact, famous inventor Thomas Edison believed the optimal rate for our perception was 46fps). However, film stock was quite pricy, so the economical solution was a compromise between how much material would be needed and the number of frames per second capable of creating an acceptable realistic motion. Namely: good old 24fps, which became the industry standard.

Since “The Jazz Singer” in 1927, the majority of films have been produced at 24fps. So, of course, we grew accustomed to this look. It has nothing to do with the “authentic” perception of reality (and that’s why most computer games and VR experiences have a considerably higher frame rate). Just like in the case of anamorphic lenses, 24fps became a subconscious sign of “quality” cinema for the audience because this stylized version of reality is traditional for film. Some tried to rebel against this convention. Thus, Peter Jackson famously released his first “Hobbit” movie in 2012 at 48fps, but it just didn’t feel “right” to the viewers’ eyes.

Higher frame rate for slow motion

So, cranking up the numbers just for the sake of it might not be a wise decision. What a higher frame rate did bring to the table, though, is the ability to manipulate time. I’m talking about slow motion, a widely famous cinematography tool.

Originally, this effect was created by running the film through the gate faster than the standard but then projecting it at “normal” 24fps. (We use the same principle now in digital cinematography as well). The higher the frame rate the movie is shot at, the slower the motion appears. We associate it most frequently with action shots, which include explosions, shootouts, and other intense, fully-packed scenes. Lately, however, higher frame rates have penetrated even mundane commercials, and we suddenly see business people in a meeting, talking to each other in slow motion while the camera revolves around them. For some cinematographers, it feels convenient because the smoothed-out movement can cover occasional camera shakes or other problems.

Overusing slow motion in random scenarios is for me a sign of either lazy operating or bad taste. In my opinion, it’s better to get a decent gimbal or go for a handheld look.

Save slow motion for emotional moments

You see, slo-mo is a rather powerful effect, which feels as if time freezes, and the speed of the surrounding action slows down. It releases an emotional reaction and works as an emphasis for dramatic moments. For instance, let’s take a look at this scene from Martin Scorsese’s “Raging Bull”, especially paying attention to the fragment from 02:05:

Here, inside the boxing ring, the intensity of the action is so high filmmakers could have gone for slow motion in the entire scene. However, they saved this effect until the moment when Jake La Motta became weakened. Suddenly, reality slows down, and we see the world through Jake’s eyes until the final blow is delivered. It’s a change of narrative perspective from objective to subjective, and it even increases sympathy toward the character. Had it worked if film creators hadn’t used slow motion with care? I doubt it.

Another example, when slo-mo brings us inside the character’s head, is the famous sequence from Sam Mendes’s “American Beauty”:

Here, the change of time feels surreal, even dream-like. It is indeed a dream, a desire, a feeling of being in love, that the protagonist emerges in. Emphasizing it with a different frame rate adds a further layer to the visual storytelling.

Creating universes where time runs differently

The possibility to manipulate time also allows us to build cinematic universes where physical laws differ from our ordinary reality. Of course, we all know iconic bullet time sequences from “The Matrix”:

Technically, creators approached slow motion differently here. They combined images from 120 different still cameras and two video cameras, which gave them the freedom to create dynamic camera movements in post-production. If you’re interested in the rig they built and the VFX workflow, you can learn about it in the subsequent video:

Another example of incorporating slow-motion shots into the narrative itself is Christopher Nolan’s “Inception”. The effect emphasized in this epic movie is how time runs differently in different layers of the dream the characters navigate through:

The most impressive moment here is, of course, the car falling down from the bridge. They filmed this sequence (and other slow-motion footage) with a Photosonics 4ER camera, frequently at 1000 or more frames per second. Fun fact: this camera was initially used in the 1960s and 70s for photo instrumentation applications, like documenting launchings of NASA space vehicles.

Using different frame rates for intensity purposes

As I already mentioned, slow motion is great for communicating the sheer intensity of a scene. If a lot is happening, slowed-down shots will allow us to see the finer details. A good example is this scene from “Pirates of the Caribbean”:

At the same time, you can use different frame rates, even within one shot, if you want to emphasize the speed of transformation. This effect is called frame rate ramping or speed ramps (a more commonly used name). It occurs when you start playing the clip at one pace and slow it down (or accelerate it) mid-action.

Another common tool everyone needs to know in regard to frame rate is timelapse, but we’ll talk more about that in our upcoming article on shutter speed.

Fast motion for time compression

We can’t wrap up this text without mentioning fast motion, can we? As the name suggests, this effect is the opposite of slow motion, and it takes place when the capture frame rate is lower than the projection one. Here’s what the book “Cinematic Storytelling” has to say about it:

As it breaks the veneer of reality, fast-motion scenes are immediately separated from the rest of the film. Consequently, fast-motion is reserved for those moments that need to be especially highlighted. Fast-motion is often used in comedy, but can also be effective in drama.

One example of using fast motion technique is the DIY scene from “Amélie”. In it, the protagonist forges a letter from her landlady’s lover to help her heal a broken heart. The entire film is filled with magic realism in mind, so the director regularly uses exaggerated effects like this one. Here, fast motion achieves time compression. It fast forwards us through the process right to the result:

Just like slo-mo, fast motion can immerse us into the altered reality perception of the characters. That’s why this tool is a frequent guest in Darren Aronofsky’s “Requiem for a Dream”, alongside his famous rapid-paced montages.

Characters of this film are constantly looking for relief from their addiction. When they finally get to it, the time in their perception speeds up and passes so quickly that they barely manage to enjoy it. And the circle begins anew.

Frame rate: the pulse of cinema

Knowing the rules and conventions is important. Using this knowledge to break them with intention is where filmmaking magic begins. We might have stuck with 24fps because of its familiar look. It doesn’t mean that we can’t use different frame rates to alter time, emphasize intense dramatic moments, or achieve a strong (positive or negative, doesn’t matter) reaction from the viewers.

What is your approach here? Do you use slow motion sometimes just for the sake of it, or do you always think about the purpose of the shot and how to execute it accordingly? What frame rate is your go-to one? Let’s talk in the comments below!

Feature image: film stills from “The Matrix” by the Wachowskis (1999), “American Beauty” by Sam Mendes (1999), and “Pirates of the Caribbean” by Gore Verbinski (2003).

Full disclosure: MZed is owned by CineD

Additional source: “Cinematic Storytelling” by Jennifer Van Sijll, 2005.