Netflix’s Adolescence is a four-part mini-series, and each episode (40-60 minutes long) is filmed in a single uninterrupted take. Shooting an entire episode as an extended “oner” is the kind of challenge that can either unravel completely or result in something uniquely immersive. Adolescence took that risk – each episode was shot in one continuous take, with no cuts and a whole lot of preparation behind the scenes. So how did they do it? What were the technical challenges – and why does it matter? Let’s have a look.

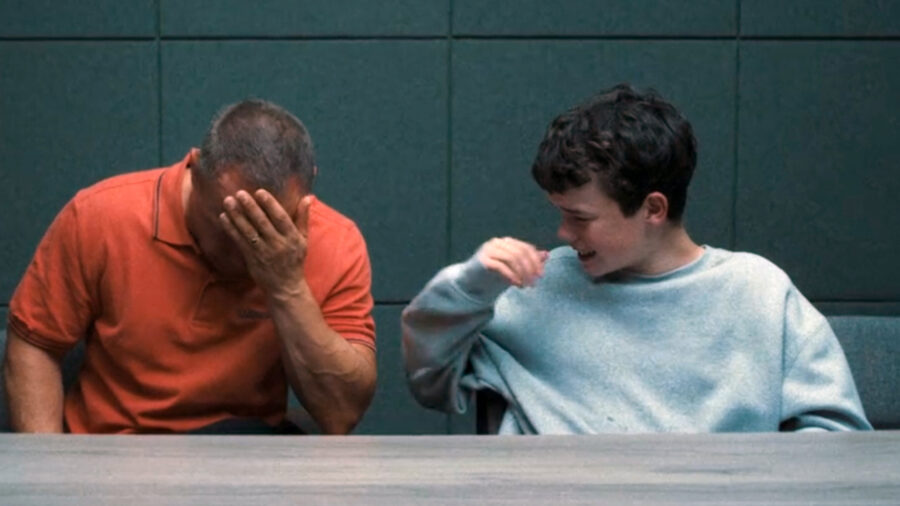

Let’s start with the story. We follow Jamie Miller (wonderfully performed by Owen Cooper), a 13-year-old boy arrested on suspicion of murdering a classmate. Episode one opens with a police raid on his home and unfolds in real-time, from officers breaking down the door, marching up the stairs, and moving past his family to Jamie’s arrest and interrogation at the police station. The camera never stops moving – every line, transition, and interaction is precisely choreographed.

Even if the coming-of-age plot didn’t initially hook me, the way it was filmed did. I’m not usually a binge-watcher, but I watched all four episodes of Adolescence in one go. It took a minute for me to get into the story, but I couldn’t look away – the filming technique was a story in its own right. In episode two, for example, I suddenly found myself looking down on the action from above. Had I missed something? A drone shot? How do you do something like this mid-shot and keep it seamless? Patthegrip shows you exactly how they did it on Instagram.

Enter the DJI Ronin 4D

In the case of Adolescence, I believe the story – the why – matters more than the how. That’s the heart of all creative work: telling something that matters. But, in this case, the story couldn’t have been told, or not nearly as specifically as the writers/creators intended, without a specific vision and a camera that could keep up. That camera was the DJI Ronin 4D (our full review of the Ronin 4D 6K here, first look review of the 8K version here, and Lab Test of the 6K here). Unlike traditional setups that rely on separate gimbals, focus pullers, and stabilizers, the Ronin 4D is an all-in-one system with a full-frame sensor, LiDAR autofocus, and 4-axis stabilization.

That last bit – Z-axis stabilization – was key to smoothing out the natural bounce of handheld shots. It let Matthew Lewis, the cinematographer, walk through the school hallways and up narrow staircases without rails or external rigs. Wireless monitoring also meant fewer people were needed on set, which was essential since the crew had to stay out of sight. In case you missed it, we gave both versions of the Ronin 4D an in-depth review (6K version, 8K version), so if you want a technical breakdown, it’s worth a read.

In the beginning

Jack Thorne (co-creator and co-writer, along with Stephen Graham, who also plays the father) says the story is not a whodunnit – it’s a why-dunnit. The point is to see Jamie and his family not as “other” but as a family we recognize much like our own. But how do you create that connection with an audience? On the YouTube channel Still Watching Netflix, Thorne said the one-shot format did two fundamental things for him as the writer. First, it imposed structure – something close to how it works in a stage play – time, place, and action are confined to a single, uninterrupted flow. That constraint forced each episode to unfold without the freedom to cut away or shift the point of view. You’re just there.

Key to single, uninterrupted takes – preparation

There’s only one word for the kind of preparation a project like Adolescence demands: meticulous. Every location had to be mapped in detail – not just for blocking actors, but for navigating transitions without breaking the shot. In Screen Daily, director/producer Philip Barantini said he and Matthew Lewis had to plan much further ahead than on a typical production, even using scale models – like one of the police stations – to work out camera movement in advance and to see what was physically possible.

We shot each episode in three-week blocks. We’d have a week of rehearsal with me and the actors; a week of tech rehearsal with the whole cast and crew; and then we’d do two takes a day for the final week so 10 takes in total. Sometimes we’d have to stop and go again, and that was one take, so for some episodes we did up to 16 takes. It usually ended up being the last take that we’d use.

Philip Barantini on filming Adolescence

Actually, turns out they needed more than 10 takes for every episode apart from the first one:

Can you imagine how tough it must be for cast and crew to be on take 13 of the same shot that takes an hour each?

The intent behind Adolescence

So what were the creators aiming for – and why has this story stuck with me long after watching? Initially, Stephen Graham posed the question: how do we tell the story in four 1-hour shots, and how do we remain as impartial as possible? But the ultimate question, as Jack Thorne says in Still Watching Netflix, is: “How did this boy end up in this place?“

As stated above, the story confronts how something like this could ever happen to a family so much like our own, or at least a family we can easily recognize and relate to. To do that, the filmmakers chose to step back. No cuts, no cues to tell us what to feel, no manipulation. The way it was filmed allowed me, as the observer, to stay completely present. That sense of being there, ultimately, is what makes the story that Adolescence conveys work as powerfully as it does.

Why it matters

It matters, because conversations start in different places and for different reasons. Whether you’re a parent with a young child just discovering social media or a teen navigating school and identity (I’m thinking “incel,” which is a term I had never heard of), Netlix’s Adolescence gives you a way in. It asks how something like this could sneak into a family without anyone noticing. Yes, bullying is something we’ve all heard about, and negative influencers on social media platforms are something else we are aware of. But shooting Adolescence the way they did has allowed us to enter the conversation wherever we are, and most importantly, in real-time.

So, ask yourself, where and when should we be having these conversations with each other and our children? Do we look at our family, our children, and our schools and think we are exempt? That nothing like this could ever happen to us? Watch Adolescence. Let it sink in. And think again.

Our filmmaking education platform MZed offers tons of courses to guide you to a point to be able to execute meticulously planned one-shots. The courses we would recommend for that are Vincent Laforet’s Directing Motion, Alex Buono’s Visual Storytelling 2 and Philip Bloom’s Filmmaking for Photographers.

Have you watched Adolescence? Do you think the one-shot format made the story more impactful – or did it get in the way? Do you think other stories would benefit from being told in real-time without the safety net of cuts and edits?