Lighting should be believable and motivated—or at least, that’s what modern filmmaking conventions say. We have already talked a lot about it and how to achieve it. After all, emulating light is a crucial skill for lighting designers. However, how about breaking the rules? What if we want to use unmotivated light deliberately as a storytelling tool? Let’s take a look at some examples that may help us on this mission.

Like many other filmmakers, I sincerely believe that all tools should support the story. Of course, lighting is no exception. When it’s motivated, it helps the audience immerse themselves in your created world without being distracted, and we will discuss this below. But what if the distraction is intended or even desperately needed?

Motivated versus unmotivated light

When we talk about motivated lighting, we mean believable lighting, cohesive lighting, and authentic lighting. In short, film lights that can be justified within the shot. Sometimes, filmmakers use practicals for this purpose: Say, if you want to illuminate the background, you can place a small lamp within the frame to create the illusion that it’s casting the necessary light. In other cases, we rely on common sense. If there is a window in the room and the viewers know about it, they will believe the daylight falling onto the actor’s face from that direction.

Of course, natural lighting is the most believable, and we can surely use it as well, but not in all cases. (You can read more about why that’s so here and here.) So, when we apply film fixtures to illuminate the set and get the correct exposure, we try to emulate the light appropriate for the situation as much as possible. This way, the lighting creates a believable world for the audience to dive in.

The Language of Lighting

Unmotivated lighting, as the name suggests, is the opposite. Imagine a shot where the light feels random, comes from weird angles, is too bright, or doesn’t fit the situation at all. That would be distracting, wouldn’t it? At least, it won’t add realism to our cinematic world.

However, as the cinematographer and educator Tal Lazar suggests in his MZed course “The Language of Lighting”, realism is not the only big force motivating lighting. The second one is the story, and the story can call for something completely unexpected, rare, and irrational.

It wasn’t always the case

Let’s start with the fact that this demand for realism wasn’t always on the radar in filmmaking history. In the early Hollywood films, you will often see the opposite. For example, Tal Lazar shows us a scene from the 1942 film “Mildred Pierce.” Look at a couple of still images from it below. Can you spot something weird about the lighting?

Film stills from “Mildred Pierce” by Michael Curtiz, 1945

The first shot is dark and moody, suggesting that there is almost no light in the room behind Joan Crawford, who portrays the protagonist. However, when she turns around and goes inside (picture 3), she is suddenly beautifully illuminated. And her close-up shot has soft, even lighting coming from a very specific high angle. Makes no sense, right? Well, that’s because the only motivation for light here is the convention that existed at the time and dictated how the star – and specifically the female star – should be lit. Thus, if you watch old movies, you will notice that all close-up shots follow the same lighting design.

Nowadays, we have much more freedom. In most cases, actors are okay with even very unpleasant lighting on their faces as long as it supports the story and their character-building. And so is the audience.

Unmotivated light today

As Tal explains in his course, story doesn’t always equal realism. Because we have such things as subtext, the emotional journey of the characters, and underlying mood, we can decide to use light to support them instead of emulating reality. Here are some film stills from the drama “Middle of Nowhere,” which won the Sundance award for Best Directing.

Film stills from “Middle of Nowhere” by Ava DuVernay, 2012

What do we see here? A simple moment: a family is gathered around the dinner table. Does it feel like a friendly and loving encounter, though? I bet, even from still images – no, it doesn’t. Some angles show windows in the background, suggesting bright daylight outside. However, the darkness inside is inconsistent with that. We barely see some of the characters! The lights around the table feel artificial and unpleasant. When the mother asks “why having a meal as a family is so painful?” we know exactly what she means. The atmosphere created by this unrealistic (to an extent) lighting design supports this notion without words.

The symbolic use of the unmotivated light

Traditionally, light has a symbolic meaning representing moral goodness and a force withstanding evil darkness. So, we can use it to connect someone or something to this symbol, just like Luc Besson brilliantly does in “Léon: The Professional,” the film that broke many hearts and remains on all the must-watch lists.

At the end of Act One, we see Mathilda’s family being slaughtered. When she comes back home, she finds her young brother dead in the open door of her apartment. The murderers are still there, so she has to walk past her brother to the neighbor’s door. We – the audience – already know who lives there: a professional assassin and recluse Léon. Let’s rewatch together this painful scene, where Mathilda begs him to open the door (starting from 02:00):

What do we see here? After struggling and questioning himself about what he should do, Léon opens the door. For a moment, Mathilda is literally bathed in light, light so intense it almost blinds her.

The source of light cannot be logically explained, giving the scene an almost religious quality. In being associated with an inexplicable flood of light, especially one of this power, the assassin becomes morally recalibrated for the audience.

From the book “Cinematic Storytelling” by Jennifer Van Sijll

Unmotivated light in your face

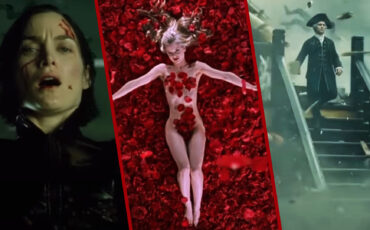

Both examples mentioned above are subtle. Although the lighting in them is neither 100% realistic or motivated, it doesn’t distract us from the scene. On the contrary, it instead supports our immersion in the story. But what if the disturbing effect is something we are after? The film that instantly comes to my mind in this regard is “Mandy.” In particular, the ending scene in the car where the protagonist, delusional, sees his dead wife sitting beside him.

Film stills from “Mandy” by Panos Cosmatos, 2018

No doubt that Nicolas Cage’s character went crazy after all the pain, rage, and killings he had to go through. We also know that he is on acid at this moment. The vibrant red color, combined with intense and completely unmotivated lighting, punches us – the viewers – in the face. The scene makes us uncomfortable (as the movie does, to be honest), but isn’t it the boldest and most suitable visual choice to support the character’s state of mind here?

Conclusion

Of course, motivating light and making it feel realistic and authentic is very important. That’s a major skill every lighting designer should acquire. At the same time, it’s also crucial to remember that you can forget about conventions when you feel that the story calls for something else. As the saying goes, know the rules well so you can break them effectively.

What about you? How do you feel about unmotivated light? Do you trust yourself to go for an unplausible lighting effect in order to enhance an emotional moment or create a certain vibe to the scene? Let’s talk about it in the comments below!

Feature image: film stills from “Léon: The Professional” by Luc Besson, 1994.

Full disclosure: MZed is owned by CineD

Additional source: “Cinematic Storytelling” by Jennifer Van Sijll, 2005.